Why Events Feel Blobby

I've been watching event coordinators (and watching myself) and I think the reason we freak out is because we lose leadership of the event. And we lose leadership of the event when the event becomes blobby.

Sometimes that blob happens onsite, when the event is in full swing. Sometimes it happens during prep and we never quite recover.

Whenever it happens, the blob is the problem and it becomes a problem for seven reasons.

Reason 1: Thinking in sequence rather than ecosystems

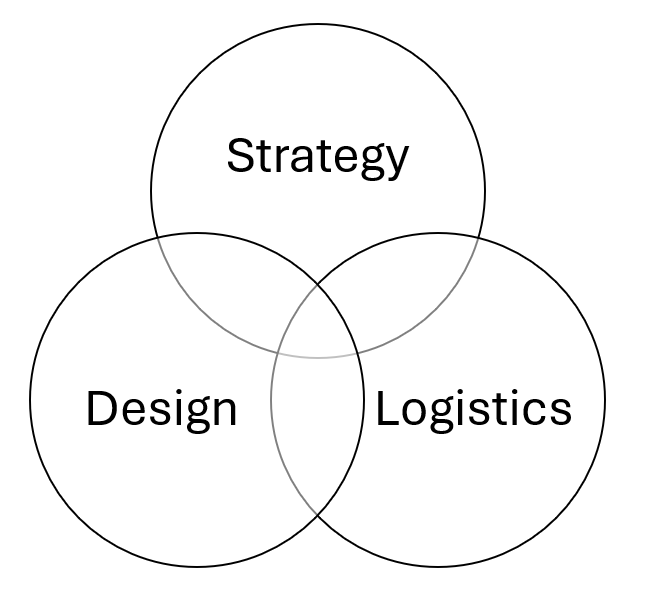

Events are blobby because the three parts of an event are not a sequence, they're an ecosystem.

When we start event planning, we think it'll go in order: Strategy, Design, Logistics.

But planning never does that. If you've ever sat in an event strategy meeting, you know how quickly it dives into discussions about napkin colors.

Why? Because strategy, design, and logistics overlap each other.

These domains are nonlinear, but events, by definition, are. So while an event has a beginning, middle, and end, the strategy, design, and logistics that power it do not.

For example, if a logistic piece breaks a design element (the ballroom we wanted isn't available on the dates we need), that can force us to rethink our strategy (either the date or the audience). That's usually when we lose the structure and the event collapses into a blob.

Reason 2: Failing to Anticipate Progressive Elaboration

The blob sneaks up on us when we don't expect the event to outgrow the plan in a natural process called "progressive elaboration".

The story of every event is that somebody has an idea on where to play and how to win (strategy). We then try to illustrate that strategy (design), then we try to implement that design (logistics). But in every step of that process, we discover more and more. This brings us back to refining and clarifyin, moving us from the simple idea to the complex plan.

This is "progressive elaboration": as we begin to elaborate the event, the event gets progressively more elaborate. Nobody likes this. Nobody wants to sit at the end of four-hour planning meeting and say, "Yep, this'll all get re-written as we move into it." But it will.

If we're not looking for it, these changes feel like they come out of nowhere, like we can't trust the plan, like we can't get our hands around it. As those changes reach deeper into the event, the original plan disintegrates and everything just starts to feel blobby.

Reason 3: Failing to Manage Temperaments

But why do changes happen in the first place?

Some if it is technical limitations (I just worked an event where the projector died and we had to scramble to set-up TVs). But mostly, changes come from humans.

Stakeholder management is 80% of an event producer's job. If I'm not doing laps around the team and proactively capturing changes, then the changes will dive-bomb the event like bats in a haunted mansion. We can't have that.

Leading the team through the changes seems simple enough, but stakeholder management is actually temperament management.

Temperaments naturally settle into the strata that give them the greatest sense of contribution. For example, to the design temperament, a logistics change will look like a design change. That's why the team will huddle around a laptop trying to solve a badging problem and somebody will ask why we even need badges. That's a good design question, but it's probably the wrong change.

With so many temperaments trying to bring change from their natural dispositions, tasks and change requests start to pile up until the whole thing congeals into a blobby mess.

Reason 4: Failing to Build for Compressed Customer Service

It's not just the team that can make things blobby, the event attendees contribute as well. Events are projects by and for people but on an uniquely compressed timeline.

If we launch a software product and our customer service is slow, then that's an issue, but it doesn't sink the product right away. Events, on the other hand, have immediate, usually face-to-face customer service demands that must be met in a matter of hours, if not minutes.

There's a reason that "Meetings, Events, and Convention Planners" ranks 14th out of 873 occupation for stress tolerance (landing in between "Patient Representatives" and "Arbitrators, Mediators, and Conciliators"). This feeling of compressed customer service makes everything feel like an emergency and there's very little time to categorize and prioritize the customer service requests.

Once the flood takes over, command goes out the window. The events coordinator that's trying arrange transportation, respond to e-mails, and mitigate double-bookings is a coordinator who's completly buried under the blob.

Reason 5: Not Plotting Agreement and Certainty

Another complicating factor is that events sit on a spectrum of "we do this every day" to "we've never done anything like this before".

If we were going to plan a hybrid event with:

- 800-1,000 in-person attendees

- 300+ online attendees

- 140+ volunteers

- Two plenary session

- 4 breakouts sessions

- Concurrent coffee and breakfast services

I'd say we have a good number of questions to answer and things to prepare.

But that's exactly what the church I serve at does every week and nobody notices because we do it every seven days. If we do that size of an event 52 times a year, our levels of certainty are pretty high. If we'd never done an event that size, our level of certainty would be extremely low.

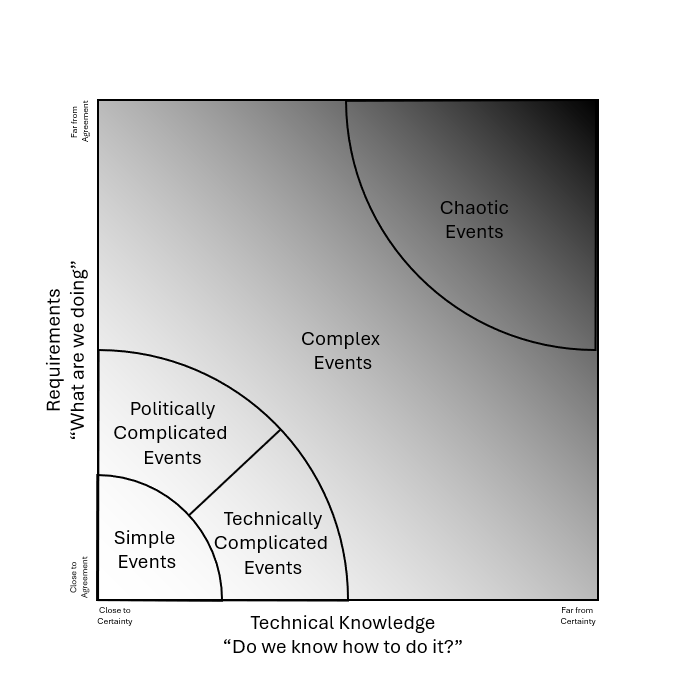

That's why we need the Stacey Predictability Model.

Ralph Stacey was a professor at University of Hertfordshire and an organizational theorist. Part of his work has been popularized into this graph (I've drawn this one specifically for events):

Along the X axis is our know-how. This is sometimes called technical knowledge, but what it represents is our certainty that we know how to do something.

Along the Y Axis is our event goals, sometimes called the “requirements”. It’s where we plot our agreement on “what” it is we’re doing.

Applying the popular presentation of this graph to events, it goes likes this:

- If we're close to agreement and certainty on what we are doing and how we are doing it, then we have fairly predictable event.

- If the team is moving away from agreement about the event, it becomes more politically complicated and we need to navigate those various desires.

- If the team knows what they want but isn't sure how to do it, it becomes more technically complicated and we need to discover more.

- If we’re in an event that is mid-way on both, that’s a complex event. We have to lead both the desire conversation (to try to bring our expectations down to certainty) as well as lead the technical discovery (to bring our know-how closer to certainty).

There are events that get far from certainty in both requirements and technical knowledge. Those are called “Chaos” events. We can lead those. It’s not hopeless. But it is a challenge.

The key about the graph is that an event moves around this chart all the time. When we can't see which way the event is drifting, we respond poorly. When we respond poorly, the event looses its structure and becomes a blob.

Reason 6: Not Putting Values into Hirerarchies

I used to think that having common values was enough to lead decision making. But over the last 15 years, I've learned that the value hierarchy is actually what leads decisions.

Be Our Guest, the Disney Institutes handbook on customer service, puts it this way:

It is, however, not enough to simply identify quality standards. they must also be prioritized. Otherwise, what happens when a conflict between standards arises?

Consider this: What should a cast member do when a guest using a walker enters a moving loading platform that governs the speed of an entire attraction? Does the cast member slow or stop the ride and inconvenience the rest of the riders, or does she leave the guest who does not fit the mold to fend for himself?

The Disney parks and resorts have prioritized their quality standards and we have just explored them in their proper order (safety, courtesy, show, and efficiency).

Once you know these priorities, the solution to the problem becomes clear. The cast member immediately knows to put the safety of the guest with disability ahead of the efficiency of the loading process, the continuity of the show, and even the courteous treatment of another guest.

Prioritized quality standards act as the guiding signals in the pursuit of exceeding guest expectations. (p. 52)

I was recently in a long discussion about an event experience over a logistical concern. We all agreed that good experience and smooth logistics were values, but how could we pick which one would win?

When we don't prioritize our values, the values will come crashing into each other, the team will argue from presumptions, and the event will collapse into a blobby mess.

Reason 7: Reacting Instead of Leading

Events are blobby when event planners lack sufficient categories for organizing and leading their project – running around trying to get things done rather than frame-working how things should get done.

When I see an event coordinator fast-walking through a venue, looking like she's about to hyperventilate, I see someone who is succumbing to the blob. When I catch myself doing it, it's almost always because I'm doing the event instead of leading the event.

Part of that is because some event coordinators are just adrenaline junkies. They don't see any reason to fix the blob because it's not a threat, it's a thrill.

But the structure-free event is also an industry-wide problem, too. While studying to sit for the Certified Meeting Professional (CMP) exam, it's shocking how unstructured the thinking in the industry is. One minute, we'll be talking about strategy, then take a sharp turn another sharp turn to beverage service, then another to the online portal, then back to strategy. It's a blobby mess.

But it's not without hope.

Categories give us thought-structures that help us parse the blob back into its parts: Design problems get design solutions. Political problems get political solutions. Customer service crushes get scale solutions. When we have the categories, we can sort and diagnose the problems effectively and from a position of leadership rather than reaction.

Events need leadership. But most of us working events don't want to lead; we want to do. And that's how we get under the blob.

Member discussion