12 Ways The Eichenwald Piece Went Wrong (and how to avoid them)

I know there’s been much said about about the embarrassing Newsweek piece of last Christmas, but I do think it can function as a teachable moment.

The piece makes a number of factual mistakes (as Michael Brown has already outlined and as others quickly noted), so I don’t want to retread that territory as much as I want to offer some direction to current and future Biblical Studies students.

The fact is, Eichenwald’s piece makes basic research and argumentation mistakes that are entirely normal for lay-level writing but entirely unacceptable for a piece claiming to be “based in large part on the works of scores of theologians and scholars, some of which dates back centuries”, as Eichenwald’s piece does.

But even the most embarrassing of mistakes can be made into lemonade if we take the time to spot the errors and commit to not making them ourselves. So in no particular order, here are a few technical errors that we, as theological and biblical studies students, should be sure to avoid.

1. Trying to Cover Too Much

Eichenwald attempts to address current events, church history, textual criticism, transmission history, translation philosophy, Greek translation issues (προσκυνέω, ἀρσενοκοῖται), creation accounts, authorship of Genesis and 1 Timothy, and theology (including gender roles, homosexuality, governmental authority, inspiration, and the trinity) all in an attempt to show that fundamentalists are hypocrites.

First off, you don’t need that much detail to show that fundamentalists are hypocrites. Examples of that abound and if anyone is having trouble finding them, they’re welcome to a coffee date with me. I have stories upon stories. And those are just about me.

But more importantly, no writer needs to cover that many topics in such a short amount of space. That’s a huge mistake.

Think of it this way, at 8,500 words, Eichenwald’s piece could be a longish sermon (a little over 50 minutes at 170 wpm). In that space, he quotes many, many scripture passages, but he cites Luke 3:16, 7:53, 16:17-18, 16:8, 1 John 5:7, Luke 22:20, 24:51, Genesis 1, Genesis 2, Genesis 6, Genesis 7 (with focus on Genesis 7:7-12, 7:13, 17, 24), Genesis 8:13, 1 Samuel 17:50, 2 Samuel 21:19 and Romans 13:1-2.

That’s 19 passages. The next time you listen to a sermon, see if the preacher gets anywhere near 19 passages.

It’s just way too much to cover such a short amount of time. A much more powerful argument could be mustered if a narrower topic had been chosen.

TAKEAWAY: If we’re going to engage in serious study, we have to pick a narrow enough thesis that will allow us do it justice and then judiciously pick our examples so it doesn’t look like we’re just hacking our way through it.

2. Lack of Appropriate Citation

I am a stickler for source citation. I’ve heard it said that undergraduates read the text; graduates students read the footnotes. I think that’s exactly right and it’s a sentiment that more people need to embrace (as in this XKCD comic).

For instance, a few claims that are of particular interest to my study that would make even the most carefree Wikipedia editor scramble for the “Citation Needed” tag would be:

- “At best, we’ve all read a bad translation—a translation of translations of translations of hand-copied copies of copies of copies of copies, and on and on, hundreds of times.”

- “The gold standard of English Bibles is the King James Version”

- “None of this mattered for centuries, because Christians were certain God had guided the hand not only of the original writers but also of all those copyists.”

- “Scribes added whole sections of the New Testament, and removed words and sentences that contradicted emerging orthodox beliefs.”

- “For Pentecostal Christians, an important section of the Bible appears in the Gospel of Mark, 16:17-18.”

- “[Constantine] ultimately influencing which books made it into the New Testament.”

- “Christian historians of the 12th century wrote that it was the pagan holiday that led to the designation of that date for Christmas.”

- “Few of the Christian faithful seem to know the Bible contains multiple creation stories.”

And so on. Those are bold claims. Bold claims that beg for a proper citation. And I really do wish that Eichenwald had included proper citation because I would love to do some follow-up research on a number of those assertions.

TAKEAWAY: We must cite our sources. No person is an expert in everything and if we’re doing a research piece, readers must be able to easily retrace our research steps. And by including those citations, you demonstrate to your readers that your work can withstand scrutiny.

3. Using One-Sided Sources

That is not to say that Eickenwald doesn’t use sources at all. He does. In fact, they are (in order of appearance):

- Pew Research

- George Gallup Jr. and Jim Castelli,

- The Barna Group

- Bart Ehrman

- Jason David BeDuhn – Truth in Translation

- Richard Elliott Friedman – University of Georgia

- Friedrich Schleiermacher

- Pat Robertson

But it is simply not scholarly to cite 8 sources in an 8,500 word piece. More importantly, though, it is a severe disservice to have such a lop-sided roster. A good chunk of the piece is spent bemoaning the theological bias of English translations. Was there not a single translator and scholar for the ESV, NASB or NIV committees who cared to comment? The only voice speaking on behalf of the “fundamentalists” is Pat Robertson, for crying out loud.

That’s just isn’t necessary.

TAKEAWAY: We should never open ourselves up for accusations of setting up strawmen. Using only extreme examples of “the other side” does exactly that. With a few e-mails, some phone calls, or even a library card, we can get reputable, thoughtful people from both sides of a question to make their best arguments for their positions.

4. Confusing Canons

If ever there was a mistake most often committed by believers and non-believers, supporters and critics it is this: speaking of “the Bible” as if it is one entity. When discussing the history of “the Bible”, that conflation simply invites confusion.

Ignoring for the moment that “the Bible” is a collection of books, the OT and the NT are two different collections of Scripture that have their own respective histories. While there is significant and meaningful overlap in the discussion, it never serves the discussion to conflate the two canons.

If we make this mistake, we’ll write strange-sounding conclusions like Eichenwald does,

Many theologians and Christian historians believe that it was at this moment, to satisfy Constantine and his commitment to his empire’s many sun worshippers, that the Holy Sabbath was moved by one day, contradicting the clear words of what ultimately became the Bible.

Sabbath was is introduced in Genesis 2:2 and is established as law in Exodus 16:23-29 and 20:8-11. And Sabbath is a huge issue for Jesus and his followers because they seem to break the Sabbath even when they’re being watched (Matthew 12; Mark 2 and 3; Luke 6, 13, and 14; John 5, 7, and 9). When confronted, Jesus refers explicitly to King David and to “the Law” (Matthew 12:3-5).

Thus it is confusing to say “contradicting clear words of what ultimately became the Bible” because there was obviously already a Jewish Bible at the time of Jesus and both Jesus as Paul seem less-than supportive of Sabbath (cf. the above gospel references as well as Colossians 2:16).

TAKEAWAY: When you are going to discuss transmission, translation or canonicity, never, never, never, never, never, never, use “the Bible” without defining it. Their stories are just so different. If you’re going to talk about the translation, transmission or canonical development of the Old Testament, do that. If you’re going to talk about the same regarding the New Testament, do that. So let’s be clear about our canons –especially when asserting they contradict each other.

5. Confusing Translations and Paraphrases

While trying to demonstrate that English Bibles impute theology into the text, Eichenwald claims,

But the publishers of some Bibles decided to insert their beliefs into translations that had nothing to do with the Greek. The Living Bible, for example, says Jesus “was God”—even though modern translators pretty much just invented the words.

Firstly, the TLB is one Bible not “some Bibles”. Secondly, we’re missing the citation on the verse in question. And finally, the TLB is, by it’s own description at Biblegateway, a paraphrase. The whole point of a paraphrase is that it’s a re-telling of the text from someone else’s interpretive perspective. Demanding translation accuracy from a self-described paraphrase is…not scholarly.

TAKEAWAY: Sadly, I’ve seen people quote and use paraphrases like translations. It doesn’t happen as often as some of my conservative brethren would like to lament, but it does happen. And it shouldn’t. If we’re trying to make a point, we should use a translation (one done by a committee and published by a reputable publisher) and make sure we consult more than one so we don’t make mountains out of molehills.

6. Quoting Half A Verse

Okay, technically, there’s nothing wrong with quoting half a verse. But when we quote one half of a verse to make a point that’s possibly refuted by the other half, we end up looking more than a little shady. As in Eichenwald’s claim,

“Do not think that I came to abolish the Law or the Prophets….” The author of Matthew made it clear that Christians must keep Mosaic Law like the most religious Jews, in order to achieve salvation.

That would seem like a good point until someone who has read the whole verse points out that Jesus said,

Do not think that I came to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I did not come to abolish but to fulfill. For truly I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not the smallest letter or stroke shall pass from the Law until all is accomplished. (Matthew 5:17-18)

In other words, a listener to Jesus might very well conclude that the passing of the law was a future event, like maybe a final sacrifice being offered to God once for all (Hebrews 10:11-15). The discerning reader might also point out that Jesus seems to take aim at the clean/unclean distinction in Mark 7:14-23.

TAKEAWAY: We mustn’t make a point from half of a verse if the whole verse could be easily read as making the opposite point. And don’t ever lose sight of the long game: writing easily refutable points will destroy our credibility in the eyes of our readers.

7. Making Ambiguous Claims

I’m pretty accustomed to lay people butchering Biblical transmission history, but a claim like “But in the past 100 years or so, tens of thousands of manuscripts of the New Testament have been discovered, dating back centuries.” is just begging for NT students and scholars to freak out.

Anyone who knows anything about NT manuscripts knows that we have less than 6,000 documented, Greek manuscripts. We only have tens upon thousands if you include every scrap of the NT ever copied by hand in any language from the 2nd century to the 15th century (see Wallace here)

But the ambiguity of the claim lead Kruger to write a rebuttal –a leading that was wholly unnecessary if the writer would simple specify which group of manuscripts he has in mind.

Besides that, I’d suggest that you can pack the same amount of rhetorical punch by saying “thousands of Greek manuscripts” as saying “tens of thousands”.

TAKEAWAY: Our claims need to be clear and documented (see #2 above). We should always say what we mean to say and be specific about our references.

8. Using Obscure Translations to Make Demonstrably Bogus Claims

Preachers and teachers across the country should get majorly busted when they pull this kind of stunt. It doesn’t happen often, but when it does, it’s usually a doozy.

Here’s what I mean: Let’s say I’m preparing a sermon and I want to make a powerful point, but nobody seems to want to translate the verse in a way that makes the point I want to make. What do I do? I dig around until I find one that does. It’s a horrible and lazy practice.

But the temptation is sometimes too great, as Eichenwald proves when he points out that,

For example, an early version of Luke 3:16 in the New Testament said, “John answered, saying to all of them.…” The problem was that no one had asked John anything, so a fifth century scribe fixed that by changing the words to “John, knowing what they were thinking, said.…” Today, most modern English Bibles have returned to the correct, yet confusing, “John answered.” Others, such as the New Life Version Bible, use other words that paper over the inconsistency. (Emphasis added)

Honestly, I thought this was a typo intended to reference the New Living Translation, but sure enough, it’s a translation published by Barbour Books.

Why point to such an obscure translation? Because all the major translations say, “John answered” (cf. NASB, NIV, ESV, NLT, HCSB, KJV, NKJV, NRSV, and NAB). In fact, even the Coverdale, Geneva, Tyndale, and Wycliffe translations read “John answered”.

It’s also worth noting that the Greek texts (NA28, Robinson-Pierpont, Westcot-Hort, Stephanus) all read ἀπεκρίνατο ὁ Ἰωάννης and the Latin Vulgate reads respondit Iohannes. In other words, no major English translation, Latin translation or Greek critical edition has included anything other than “John answered”.

So here’s my question: If we can’t make our point from any of the major English translations, from any of the compiled Greek texts or from the Latin text, and instead resorts to an obscure English translation from 1969, is it really a point worth making?

TAKEAWAY: I know it’s tempting to find a translation that agrees with us. But we must not fall into this trap. It makes us look desperate. Again, we should use translations that are translated by committees and published by reputable houses. In other words, as a general rule, stick to the big six (p. 36 of the ABS/Barna State of the Bible Report shows that the top six translations are KJV, NIV, NKJV, ESV, NLT, NRSV).

9. Making Incoherent Claims

When putting forward an argument, we have to put together connecting ideas. We shouldn’t hold to one conclusion at one point and then different, contradictory conclusion at a different point. All of our ideas need to hold together.

For example, we shouldn’t claim, “yet none of them are supported in the Scriptures as they were originally written.” if we are going to later argue that “At best, we’ve all read a bad translation”. If the second claim is true, then there’s no need to make the first. If all we have are translations of translations, then there is no way for “literalists” to read them “as they were originally written” because there is no access to the original.

TAKEAWAY: My plea to all of us is simple: pick one. Pick an argument and run with it. Don’t pick two arguments that are incompatible. Besides, picking one is a great way to tighten up the piece so it runs a little shorter.

10. Making Big Deals out of Admittedly Small Deals

Similar to point 9 above, we can sound more than a little shrill when we try to make a mountain out of a molehill. Eichenwauld quotes Ehrman saying “There are more variations among our manuscripts than there are words in the New Testament,”, then concedes, “Most of those discrepancies are little more than the handwritten equivalent of a typo” but then adds, “but that error was then included by future scribes.”

Basic question: If we’re able to look at a manuscript variant and say, “Gee, that looks like a typo.” Then why do variants matter? And if we’re able to spot it from one scribe, why couldn’t we also spot it from a copy? Do typos magically become not typos because they were copied? That doesn’t make any sense. Who cares if a scribe copies an error if you’re also telling me that we can see them? It is silly to claim something is a big deal (scribes copying errors) if you’re claiming –in the same sentence– that those errors are noticeable.

TAKEAWAY: Sometimes an argument sounds more powerful in our heads than it does on paper. Get a second set of (hopefully critical) eyes to read through your piece. That will help sift out some of those weaker arguments.

11. Making Big Deals out of Well-Known Deals

Following in the rhetorical vein of KJV-Onlyists, Eichenwauld marches out a collection of texts that were added to the Bible, concluding:

These are not the only parts of the Bible that appear to have been added much later. There are many, many more—in fact, far more than can be explored without filling up the next several issues of Newsweek.

Agreed. And Eichenwald would have served his readers well by pointing them to either the detailed list on the Wikipedia page dedicated to the subject or directing them to the footnotes in almost every major Bible translation.

Whatever we may say about scribal additions and textual variants, I think we can all agree that it should’t be a shock if they’re included in the footnotes.

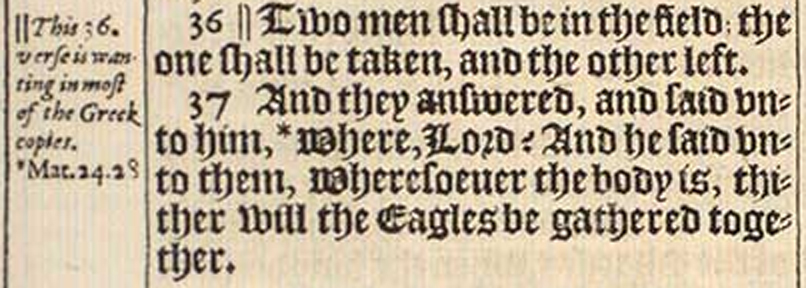

Furthermore, even the 1611 King James Bible included marginal notes about questionable manuscript support (as I’ve already pointed out here). For example, the below image shows a note for Luke 17:36 that reads, “This 36 verse is wanting in most of the Greek copies.”

Sadly, these marginal notes are not usually included in the cheap KJVs we see for sale, but the point is this: listing questionable manuscript support in English translation is a scholarly practice that is centuries old.

I should also mention that when Bart Ehrman (whom Eichenwald references in his article) was asked why people are unaware of NT manuscript issues, he replied, “My guess is that there is a simple answer: most people don’t read the footnotes!” (Misquoting Jesus. p. 253)

TAKEAWAY: The takeaway for us is two-fold: First, we need to read our Bibles. All of it. Including the footnotes. Second, we need to treat knowledge with rhetorical calm. Certain facts can have the misfortune of being readily available without earning the status of being common knowledge. And just because something isn’t common knowledge does not mean we have the liberty to present it as if it’s ground-breaking news. We can bring lay people up to speed without acting like we’ve got a scoop.

12. Lumping A Whole Community Together

I don’t know Kurt Eichenwald. I don’t imagine he’s evil or stupid. And I would posit that he has to have some kind of game to be a best-selling author and contributor to so many brand-name news outlets. Yet, with all that game, he seems to be unable to identify what all the fuss is about:

I find it endlessly interesting that some say a critique of selective reading of the Bible and an encouragement to read it is anti-Christian

— Kurt Eichenwald (@kurteichenwald) January 6, 2015

Maybe an enumerated list of quotes from the piece might help:

- “They fall on their knees, worshipping at the base of granite monuments to the Ten Commandments while demanding prayer in school.”

- “They appeal to God to save America from their political opponents, mostly Democrats.”

- “They are God’s frauds, cafeteria Christians who pick and choose which Bible verses they heed with less care than they exercise in selecting side orders for lunch.”

- “They are joined by religious rationalizers—fundamentalists who, unable to find Scripture supporting their biases and beliefs, twist phrases and modify translations to prove they are honoring the Bible’s words.”

- “The Bible is not the book many American fundamentalists and political opportunists think it is, or more precisely, what they want it to be.”

- “In other words, with a little translational trickery, a fundamental tenet of Christianity—that Jesus is God—was reinforced in the Bible, even in places where it directly contradicts the rest of the verse.”

- “Some of those contradictions are trivial, but some create huge problems for evangelicals insisting they are living by the word of God.”

- “To this day, congregants in Christian churches at Sunday services worldwide recite the Nicene Creed, which serves as affirmation of their belief in the Trinity. It is doubtful many of them know the words they utter are not from the Bible, and were the cause of so much bloodshed.”

- “The next time someone tells you the biblical story of Creation is true, ask that person, ‘Which one?’ Few of the Christian faithful seem to know the Bible contains multiple creation stories.”

- “Evangelicals cite Genesis to challenge the science taught in classrooms, but don’t like to talk about those Old Testament books with monsters and magic.”

- “Of course, there are plenty of fundamentalist Christians who have no idea where references to homosexuality are in the New Testament, much less what the surrounding verses say.”

- “Too many of them seem to read John Grisham novels with greater care than they apply to the book they consider to be the most important document in the world.”

- “This examination is not an attack on the Bible or Christianity. Instead, Christians seeking greater understanding of their religion should view it as an attempt to save the Bible from the ignorance, hatred and bias that has been heaped upon it.”

Rachael Held Evans and I don’t agree on much, but we do agree on this, “Eichenwald’s argument fails before it begins. He assumes the very worst of his opponent’s motives and thus puts them on the defensive right from the start.”

More to the point, the piece is anti-Christian because it assumes “Christians”, “Fundamentalists”, “Evangelicals”, “Literalists”, are all the same group of people who all have some kind of affinity for Michelle Bachmann, Sarah Palin, Rick Perry, Bobby Jindal, and Pat Robertson. In other words, he seems to be judging Evangelical Christianity because of what he’s seen on TV.

Almost one out of every 5 Americans self-identifies as white evangelicals. To suggest that we are all cool with TV evangelists, Pentecostal snake-charmers and opportunistic politicians is to demonstrate how little one knows about the rich, intellectual diversity and conflict within this community. That’s an especially incongruous premise for a piece that is flat-out begging people to see facts and nuances.

I was raised in a conservative (some might say fundamentalist) evangelical family that took me to both charismatic and reformed churches and I’m finally finishing a five-year tenure as a Biblical Studies major after teaching Christian apologetic for 7 years. If Eichenwald was intending for me to take a closer look at myself and my community, he would have made a greater impact if he had taken a closer look at me and community before leveling such strange and incoherent objections.

TAKEAWAY: We should treat communities other than our own with love and respect. Even if we disagree –even if we passionately disagree– the people on the opposite side of a question should at least be able to recognize themselves when they read our descriptions of them.

Conclusion

Writing about the Bible, Christianity and Christians is tough. The Bible a big book with big histories and big controversies. Christian history just multiplies those threads. And Christians are a complicated and storied group of people. When writing about these things and people, there are many, many traps and pitfalls that students must be diligent not to fall into.

So to recap:

- Pick a narrow enough topic and thesis

- Cite your sources

- Present both sides

- Treat the different canons separately

- Don’t use a paraphrase like a translation

- Don’t quote half a verse (if the second half contradicts your point)

- Use a reputable translation

- Make clear and documentable claims

- Make coherent and congruent arguments

- Submit your drafts to critical eyes

- Treat knowledge with rhetorical calm

- Write about communities in a way they will recognize

I know it’s tough to have to dig so deeply, but academic excellence is one of the best ways for students to fulfill the golden rule: “In everything, therefore, treat people the same way you want them to treat you, for this is the Law and the Prophets.” (Matthew 7:12)

Member discussion