I Give This Post 6 out of 10

I got a text message from Cori (my sister-in-law, art buddy, and independent art instructor): "What do you think about grading [subjective] material like art classes?"

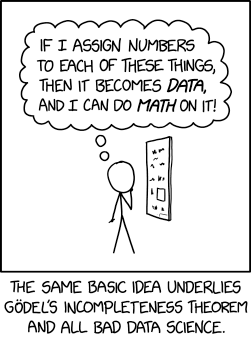

Instead of letting myself get triggered, I just replied with this comic by XKCD,

But it turns out I am powerless against this kind of bait. So, let me try to say in 4,600 words what XKCD said in a single panel.

Counting Arbitrarily

Let's start with a concession. Counting is extremely useful when we have countable things. There are 20 chairs in this Starbucks. There are six breakfast sandwiches in the display case. There is one broken light fixture. Counting countables is the task of establishing "scope". We know how many people can sit, how many sandwiches we can eat, and also that we need to buy one more lightbulb. It's kind of fun, if you enjoy being single.

We can also gain the benefits of counting even when the countable is a bit squidgy. For example, right now there's 8% left on my cell phone battery. What does that mean? Both nothing and everything at the same time.

Battery power depletion is caused by constantly fluctuating power demands from things like processors use, screen brightness, data usage, signal strength etc. At 8%, it can sit quietly for an hour or I can choose to watch a video and it'll last a few minutes. But the heart palpitations when I say, "I only have 8% left! No! 7% Ahhh!"? That's real. It means something even though that something isn't as definite as how many light fixtures we should order.

But there's a fun quirk of human nature: we like to affix numbers to our feelings as if they were countable. "Star ratings" for books, movies, and TV shows are a perfect example. Why does a movie get 5 stars? What's the difference between five and four stars? I don't really know, other than that I feel it "earned" that fifth star. But I actually just mean that I enjoyed it more than other things like it. In fact, I might say that I enjoyed it the most. But instead of just exercising my superlative powers, I say "I give it 5 stars!", as if assigning a number to my feeling somehow makes my experience more definitive.

Counting feelings starts early, too, when parents and children play the "I love you one thousand" game. It's silly because it's absurd (and all the best childhood humor is absurd), But it still somehow communicates.

That's a long way of saying I think the spectrum of counting things goes something like "things we can count" to "things we feel but try to express with numbers".

That brings us to industrial schooling. Grading is an extreme form of the "feelings as numbers" exercise. That's not a unique problem to schools. This human impulse of assigning numbers to express feelings transcends industries (Industries can have unique technical problems, but they don't have unique cultural problems because cultural problems source from deep within human nature). But grading is actually both an industry-specific technical problem as well as a human nature problem.

We'll look at the human nature question first and then turn to the technical question.

Does It Count?

It's one thing to ask, "Am I counting a countable thing?" it's quite another to ask, "Does the thing I'm counting actually representing the thing I'm trying to communicate?"

I once heard a speaker say that he didn't have 12 years of guitar experience, he had one year of guitar twelve times. I know what he means and I've been there myself, but it's worth asking, what, exactly is "one year" of guitar?

Certain progress is countable ("I ran 1,000 more meters today than yesterday."), but not all progress. "I practiced today" can mean a thousand different things to fifty different people. "I wrote today" can mean I wrote a half page of dialog or that I wrote a verbose, meandering reflection on the nature of grading. But I did write today.

If somebody sat in my practice room or watched over my shoulder as I typed, they would know what I mean. But if I stand in my lesson and say, "I practiced an hour every day this week", it's just convenient. I may still suck and the evidence of that will be plain as the lesson progresses, but hey, at least I can say I did a thing with a unit of measure that is communicable.

But the other big reason to count progress – even if it's not countable – is so I can brag about it. I practiced for four hours today. I wrote 1,000 words every day this week. I wrote 50,000-word novel in November. Praise me. Be impressed by me. Love me.

Of course, that four hours of practice may have been crap. The 1,000 words may be crap. That NaNoWriMo novel may be crap. Those numbers don't really mean anything because quantity and quality are two separate evaluations and only one is countable.

So how do we make quality countable? We assign a feelings numbers to it. "I give that practice a 7/10." "That essay is a 3 out of 5." "I give my novel 5 stars!"

What's wrong with this? A feeling isn't countable. Differentiated feelings are countable. If I'm at a wedding, I may be both happy and sad. That's two feelings. But the depth of a feeling is a not a countable. I can't be 5 happies and 2 sads.

Counting Feelings for Others

Pain assessment is fascinating rabbit hole we won't go down, but the short version is that feelings are real and consequential, so we need to communicate them. I was recently in the ER with my nephew and because I was able to spend an hour with him, I knew the severity of pain he was in. The doctor who walked up to help had to a quick assessment and doesn't have the luxury of that kind of time. When my nephew said his pain was a 3, that's helpful for communication, but the one thing we can say for sure is that pain cannot be a "3". You can count how many times you say "ouch", but not how deep that ouch goes (and just so I've said it, my nephew ended up being fine and we bought ice cream on the way home).

This gets into the paradox of counting feelings: since a feeling is not a countable thing, the numbers are meaningless. But we also know they still communicate. So meaningless things are communicating meaning. How is that possible?

I think it's because we've substitute numbers for words. I've been sitting here too long so my bum is a warmish sort dull hardness that gets prickly towards my tailbone. I can say that or I can say it's a 0.5 and isn't that easier...and less awkward?

The Problem of Grading

That brings us to grading. My objection to grading is that it counts feelings, which is useful for communication, but then builds an entire industrial infrastructure on top of it as if the feelings were reliably countable.

We grade for the same reason we rate restaurants and pain: to communicate feelings to outsiders. But since feelings aren't countable, the grades are actually meaningless.

As a student, I have received (or earned, depending on whom you ask) every letter grade on the scale. Borrowing from Sorkin, I can honestly say that I've made both Dean's Lists. But most of my teachers and professors (the good ones, anyway) have never been disappointed or even alarmed by my "grades", they've always confronted me about my performance. And those discussions centered around, not why I wasn't getting the material (which I almost always did and they knew it), but why was not performing according to the expectations of the rubrics – standards with which they occasionally disagreed.

As a teacher, I had one student get 103% in my class, though I wasn't really sure about her engagement with the material and I had a student who struggled every week to scrape out his Bs, but worked as my teaching assistant the next year.

Those experiences taught me that grades can be a helpful for troubleshooting, but not a definitive answer to anything. Discussing pain assessment in their monograph, NPC says, "Although pain classes are not diagnoses, categorizing pain helps guide treatment" (p. 1o). That's how I view assessment tools: as guidance for better treatment, not as the whole picture of the student. I have never needed a letter grade, quiz, or test to tell me how one of my students is doing. I knew that because I knew them. But if, in a series of quizzes, they suddenly or consistently get fewer questions correct than I'd expect, that's interesting to me and I'd like to know more about what happened. It's the first step to bettering a student's knowledge acquisition and development.

To that end, I'd like to distinguish between "assessment" (which uses feelings numbers to create a feedback loop for better instruction) with "grading', which is a mechanical process where the feelings numbers are used – not as a helpful tool – but for purposes of evaluation.

Grading for Strangers

In real-world use, grades exists because relationships don't. The only people who have ever taken my grades seriously have been administrators – registrars, academic deans, admissions "counselors" – the people who don't know me, don't know where I started, where I've grown, where I've struggled. People whose expertise is not me, the student, but rather me, the paperwork.

Teachers don't need grades; administrators do. Occasionally parents, too, if they're particularly disconnect from their students or just have a mad crush on getting those School Points.

These people are strangers to the student. They need the people in the classroom to assign feelings numbers so they can sit in their offices and evaluate the work without leaving their office.

Practically speaking, that's all grades are used for – which is ironic because grades are actually crap at that.

The Stupid Maths of Grading

I mentioned that grading as a industry-specific technical problem and here it is. As a life-long lover of data and analytics, grades are particularly grating to me. School administrators function as a class of professionals whose decision-making dashboard is populated by useless data. Not bad data, useless data. And they spend their entire careers living in it.

Administrative logic goes something like this: we can determine macro trends in student progress if we can quantify student progress over time. Therefore, we will mandate a series of instruments that measure knowledge acquisition and from that data, we can produce a trend line quantifying both our students' and teachers' success or failure (rarely the administrators' success or failure, by the way, but that's a different topic).

That sounds good except that this process doesn't do that.

To see a trend, we'd want to measure the same question over time to get an accurate reading (for example, the classic, Net Promotor Score question, "Would you recommend our services to a friend?"). But that's not how quizzes are written because that's not how curricula are written.

A course doesn't reinforce the same information over time, it introduces different material sequentially. This means we have to ask a different question with each data point. But then how is that supposed to produce useful data?

Lets take quizzes as an example. If a student quizzes like this:

Module 1: 90%

Module 2: 90%

Module 3: 60%

Module 4: 90%

What does that tell us? I have no idea. The student may have struggled with the material in Module 3 or his childhood dog (a gorgeous golden lab – the lifeline throughout his parents divorce and abandonment and then his faithful companion during the death of the beloved grandparents who took him in) died of old age the same week that his high school sweetheart dumped him for best friend who lied to him about it.

Hey, as long as we're making up a story about this data, we might as well make it a juicy one.

But this is the critical point: it takes no more imagination to say that the student struggled with module 3 than that all that stuff happened with his dog and girlfriend. One is not more reasonable than the other. Both are complete fantasies.

The only thing we could say about this data set is that the percentage points of module 3 is down 33.3% from the previous and subsequent modules.

That's it. That's all the data say.

Maybe that module is bad. Maybe it was just bad for that student. Maybe there was substitute teacher that biffed the instruction. Maybe there was error in the grading rubric. Maybe there was a glitch in the LMS. Maybe, maybe, maybe. It's just data. It can tell us that, not why. The number is about as useful as the 8% battery indictor on my phone.

More importantly, I made these data set up. It represents nothing in the real world. The conclusion-jumping compulsion that a data set can generate is powerful and our pattern-finding brains are stoked to ride the blast.

Think about it: this data aren't from a math class, or a writing class, or a science class. It's not from anything. I made it up. And yet we've just finished a whole discussion about what they could mean.

That's the power of our story-making brains. And if data have that kind of power when they come from nothing, what kind of power do they have when we think they come from something?

The "Something" Administrators See

But do you know what's insane? The administrators never even see the trend line. Instead, they average the results. They take data points from a class and combine them and then trendline those results across disparate courses and that becomes their basis for evaluating the student.

So the only possibly useful insight from this inherently flawed exercise – seeing change over time within a course – gets completely washed out as all the data is combined, both diluting and polluting the data pool. And then that crappy data is used to create a new evaluative metric – there's not even a trend line.

It's so crazy I can't even believe it's true – and I've actually done it myself and worked alongside other professionals who do it for a living. It's the standard practice and it's insane.

I know some of you maybe aren't following how stupid this is, so let me illustrate the point: Lets take the pretend quiz example from above and say each of those module quizzes was 10 questions for 40 points possible.

Student A could look like:

Module 1: 9 points

Module 2: 9 points

Module 3: 6 points

Module 4: 9 points

Total: 33/40 = 82.5%

Student B could look like:

Module 1: 8 points

Module 2: 8 points

Module 3: 9 points

Module 4: 8 points

Total: 33/40 = 82.5%

Summing the results obliterates any possible insight we could have had from the dataset by making an A student who had a one bad day look the exact same as a B- student.

Does the administrator know any of this? No. Because the only thing submitted to an administrator is the averaged number.

But it gets worse. The average of those scores are then placed next to the average of the scores from totally different (usually unrelated) courses and then those scores are averaged again. And that becomes the students "Grade Point Average", the ever holy determiner of the student's position in the current school and all future schools.

It's as if we wanted to count how many different colored Skittles there are and chose to do so by dumping them all into a paper bag.

It's bananas.

Why do we keep doing it? So decisions makers (who think they have no other means of getting some kind of evidence for their decision making) can still feel like they have an evidentiary base for their leadership. I'm happy to grant that counting arbitrarily can be useful for communicating to people outside the room and grading is supposed to do that, but it doesn't. In fact, it fails so miserably at this one task, it should be scrapped altogether.

What Scrabble Taught Me About Gaming

But the question was about grading art. To answer that question, I have to tell you about the breakthrough I had with Words with Friends, aka Internet Scrabble.

About a decade ago, Words with Friends was in its heyday and several people asked if I'd play them. I was sort of down on social media in general and social media games in particular (this was also the time that Farmville was hugely popular for inexplicable reasons). But words and language are a source of pride for me, so I figured I'd be amazing at it.

I sucked.

There I was, having wrapped myself in a writerly identity and I couldn't even beat freaking amateurs at a word game. It was humiliating.

Thankfully, after a few grin-and-bear-it defeats, I had a breakthrough. I was losing because I had fewer points.

Some of you may think that's not as big a breakthrough as maybe I feel like it is, but think about it. If you're losing a game, it's because your opponent has acquired more points than you within a particular set of parameters. So all I have to do to win is get more points.

I'm like a genius, you guys.

Once I switched my thinking from finding words to finding points, I began to dominate. My opponents were as shocked as they were frustrated. How did I keep crushing them? I knew my secret answer: I had learned that Scrabble isn't a word game; it's a math game.

Gaming Art

Grading art is the act of gaming art. It assigns numbers to squares and tells students that if their art lands on a particular square, it will result in more School Points.

In my view, that is a horrific way to teach art.

Many people think the battle is between art and commerce. It is not. The battle is between art and points. Money is just one form of points. There are other points like "clicks" and "views" and "audience retention" and "Rotten Tomato Scores" – all forms of saying, "You may know how to spell 'spatula', but 'cat' on a double word score is still worth more." The most egregious of these are School Points. They are worth nothing except the opportunity to earn more School Points. And they teach arts students to paint by numbers.

But that's not what art is for. Art is risky. It's risky to pick up an instrument because you might play a wrong note. It's risky to stand up and sing because you might sound bad. It's risky to put your thoughts to paper because you might say something stupid or worse, spell something wrongly (I look forward to your e-mails).

Making art is the act of taking a risk – putting your unique, God-given, God-designed, pain-forged worldview on display in front of a deeply unsympathetic and cynical crowd who all see the world differently and may say your perspective is somehow deficient.

Do you know what doesn't help that process even a little bit? "Yeah, I give that poem a B+". It's obnoxious when film critics do it, and it's obnoxious when teachers do it.

At the end of the semester, an art student shouldn't have a grade; they should have a work of art. And if their work of art demonstrates their acquired skill, what does a grade contribute? What would happen if I admired painting then notice that it got a "B"? Nothing. If I a piece speaks to me, it speaks to me. If somebody feels differently, that's what art is for. But a score isn't an argument. If we want to debate a piece of art, let's do it. I'd love that. And I think the budding artist would benefit from hearing that debate (certain writing programs work like this), but they don't benefit from a single perspective having the last say on their work.

Real Art Education

Teaching art is not about points, it's about a transcendent experience after years of focused apprenticeship.

When I had a studio, I'd stand beside my student while she sawed away at a piece, mirroring her movements, yelling instructions, urging her on as she tried to find the tone and expression she wanted so badly. And you could tell she wanted it. Hair pulled back. Head heavy on the chin rest. Her bow arm weighted, placed, balanced. Her fingers working up-and-down the fingerboard. A thousand, micro decisions every measure as her unblinking eyes raced from one end of the page to the next. Four minutes later, she'd land on the final note, bow in the air, sparking a giant, full-throated "Yes! Just like that!" from me. But I didn't need to say anything. She knew she'd nailed it. You could see it in her face. She could hear how much better she had become at her craft. She could feel it pulsing through her musculature and bone structure. Most importantly, she could feel it in her soul. She had found not just her technique, but her art.

Like most students, in the afterglow of that success, she would often try to mask her pride by pointing out her mistakes, like I hadn't noticed them. Of course I had. I also didn't care. Because in that moment, I had heard the culmination of her commitment, her work outside the studio. Her humility, her diligence, her persistence. I'd seen it all in a one hour lesson, every week, through winter, spring, and summer, for four years. All of it had turned her into a musician.

So to all the people asking how to grade art, I ask them: what number am I expected to affix to that experience?

The School's Answer

Five. That's the answer I was asked to give.

I taught music students privately (because so called "extra curriculars" come dangerously close to pay-to-win, just like college entrance exams). But a local, public school needed outsiders to come to their end-of-year evaluations and so they brought me in as ringer for the day.

As the head of music education trudged down the hall, leading me to my classroom for the day, he explained, "The scores go from 1-5, but nobody gets less than a 3." If memory serves, I may have had something like 15 minutes with each student. I certainly didn't need that kind of time to stamp a three point scale onto a student; I can probably give that evaluation just by how the student holds the instrument.

So the students would come in, play a quick piece for me, and then we just spent the rest of the time doing a mini lessons. They'd leave and I'd judge them with a score, a score I knew meant nothing to anybody who mattered and everything to the poor students. But The System needed numbers so administrators could do math. The teachers understood the implications of those numbers so they knew how to game the math. And as a day-player, I knew I couldn't do anything about any of it, so I just taught the student in front of me. In retrospect, I imagine that's what all the good teachers trapped in this stupid game do, too.

What's the Alternative?

Grading is the circulatory system of Industrial Schooling. Everything from minutia like whether or not a teacher gives an extension on an assignment to state laws around educational neglect and even up to federal legislation determining funding are all built atop grades. How, exactly, could the system operate if it was starved of these grades, no matter how meaningless they actually are?

The grading system and school system are so co-dependent, I'd argue that the grading is the school system. Because of that, people can't acknowledge how profoundly meaningless the data are. If we did, the entire system would collapse.

But that hasn't kept education professionals from taking swings. Candidly, I haven't taken a dive into this world, but it seems like some so-called "ungrading" solutions are actually "grade hiding solutions". I'm open to it, but color me skeptical. I don't understand why contract grading would produce less stress or less assessment-focus on the part of the students. Narrative assessment seems like an interesting way to try and communicate actual student achievement, but I've also worked in technology where documentation is notoriously difficult.

I'm also concerned that my tribe of conservatives will mock any attempt at assessment reforms. Wasn't it just a year ago that every republican in Oregon was up in arms because somebody pitched the idea of eliminating standardized testing? Granted, the timing was more than a little suspicious after the school system received a profoundly embarrassing report on education during COVID. But what baffles me is when my tribe – the pro-homeschool and anti-teacher union, pro-education reform tribe – suddenly had nothing but love for top down, centralized achievement testing. If I've learned anything in politics, it's that one should never waste a crisis. If academic achievement sucked during COVID (because of course it did) and suddenly every working professional in the sector decides to changes the rules on how that assessment is made, I'm on board if it means we can jettison a crappy system, I don't care how self-serving it is for education professionals. The enemy of my enemy is my friend.

But no, today's Republicans love achievement testing and attaching funding to it because my party has completely lost the thread on educational policy.

But whatever. Policy making is a long process. We have time. It's just sad to me that grading will continue to fuel a horrible schooling system in the mean time.

That's why the XKCD comic explains the grading scheme so well: grading is arbitrary data collected from arbitrary instruments which, even if it could demonstrate anything (which it barely does) is then summed into a total that strips out any actionable insights from the data. That is a ton of work for both educators and administrators, it's the fuel for the massive machinations of the school system, but it's all meaningless. We just keep pretending it means something because the only other way to do The School is to not do it at all.

And that's not an acceptable answer to us. Not yet, anyway.

Member discussion