Pastors and Teachers: It's Time To Let Your Greek Show

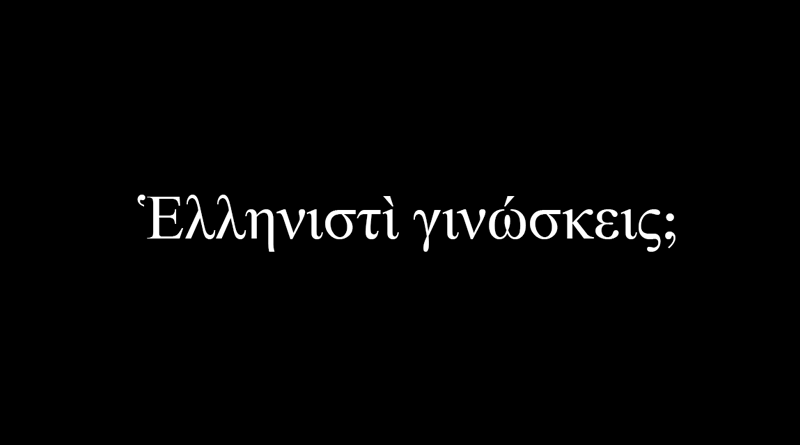

I was out on the front porch doing an “Open Forum” with our students when a young man asked me if I thought it was better to study out of one version or do a comparison (he meant use a parallel Bible). I told him he should just learn Greek. Not at all satisfied with that answer, he pushed back, asking what the “second best” option would be. I told him again, just learn Greek.

The reason for this is really obvious. Comparing translations only shows you what the differences are; it will never show you how to adjudicate them. So, absent translation training, the only thing a student accomplishes by comparing English translations is increasing their frustration without equipping them to come to any kind of conclusion.

For example, let’s say a diligent student compares John 1:18

| KJV | NIV | NASB | ESV |

| No man hath seen God at any time; the only begotten Son, which is in the bosom of the Father, he hath declared him. | No one has ever seen God, but the one and only Son, who is himself God and is in closest relationship with the Father, has made him known. | No one has seen God at any time; the only begotten God who is in the bosom of the Father, He has explained Him. | No one has ever seen God; the only God, who is at the Father’s side, he has made him known. |

So, here we see:

- The NASB and KJV read, “At any time”, a phrase that is missing from the NIV and ESV

- The KJV read, “only begotten Son” while the NIV reads “One and only son” and the ESV reads, “the only God”.

Or, because it’s fun, let’s say the student is very diligent and actually compares the 1984 NIV with the 2011 NIV:

| NIV (1984) | NIV (2011) |

| No one has ever seen God, but the one and only Son, who is himself God and is in closest relationship with the Father, has made him known. | No one has ever seen God, but God the One and Only, who is at the Father’s side, has made him known. |

Why change “the one and only Son” with “God the One and Only”? Why change “closest relationship” to “Father’s side”? How is the student supposed to know? The answer is, they can’t. They’ll be forced to trust commentators and online articles. That’s as close as they’ll get to an answer.

What is the diligent student supposed to do? Read some commentaries and hope there’s a scholar that he or she trusts enough? No translation explanation is going to make sense to someone who hasn’t been trained in it. So hopefully the “layman’s” explanation is clear enough and the source is trustworthy enough that the student can just go with it.

But the student will never really know. Not for themselves, anyway. Instead, all their theological conclusions will end up in some kind of appeal to authority.

The student at the Open Forum did not seem happy with my insistence that he spend his time learning Greek (as opposed to becoming an expert in the discrepancies between English translations, though it is very telling that –in his mind–that’s what serious Bible study entails), but I was honestly hoping to spare him the frustration.

However, we need to be honest about what his Greek learning experience will be. He’ll have great professors who will take him through a standard text (Mounce or Black or whatever). Class will be fun. In a college setting it’ll be 3 hours a week and a lot of homework. This will mostly consist of memorization. Lots and lots and lots of memorization. If he survives it, he’ll eventually start translating the Gospel of John. Then maybe Mark. He’ll probably never get as far as Hebrews. He’ll have some good vocab (probably to the sixtieth usage, if he’s super diligent), a ton of verb endings, participles coming out his ears (a project that’ll make him wish he’d done a better job learning the noun endings).

Then it’ll be the end of class. And he’ll go about his life only using his Greek when he’s studying by himself, reading technical commentaries, reading journal articles, reading blogs for advanced students.

He certainly isn’t going to use it at church. Or Sunday School. Or Bible Study. He’ll be the lone guy who “Studied some Greek”. The people around him will really admire that, but he’ll never be allowed to use it because it would be impolite. After all, Greek should give you support; it shouldn’t actually be seen.

This raises a great question, in light of that experience, what, exactly, is the motivation for a student to learn the language? Should a student learn the languages so he can keep quiet about it in church, keep quiet about in Bible study, and keep quiet about it in every real life situation he encounters?

I can sit on the Summit porch and tell a student to skip the translation comparison and dive right into the original language study (as any teacher would recommend to any student who wanted to seriously study any non-English text). But I know I’m damning him to an experience of isolation. That isolation will breed neglect and he’ll use Greek until he doesn’t any more. Paradigms will get murkier and the exposure will become less and less, until finally he just drops it altogether. “After all,” his life experience will explain, “It’s not very practical.”

And then we wonder why more students aren’t interested in pursuing Biblical languages. We we wonder why pastors “lose their Greek”. We wonder why our people can have their butts handed to them by Jehovah’s Witnesses and their explanation of καὶ θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος in John 1:1c, by Mormon Missionaries with their applications of Article of Faith 8, or Muslims with Sura 5:15.

I don’t wonder. My Christian communities deeply admire those who have studied Biblical languages but they also don’t ever want to have to see it. It’s impolite. It’s showing off. It makes people feel dumb. It makes people feel like second class Christians.

Early on in my studies, I was given this little adage, “Greek is like underwear: It should provide support but nobody should see it.”

In the last several months, I’ve concluded this well intentioned pastoral note is actually the reason people aren’t engaging their Bibles in the original languages.

Here’s what’s missing, though: real language acquisition only comes through immersion or at least consistent exposure. As long as we marginalize Biblical language discussion, we will never raise a generation of serious Bible students. Ever. People need to see languages being used before they are inspired to learn it and motivated to use it themselves. That’s how all education work, but it’s especially true with languages.

I mean, if you can’t use NT Greek in your local, Christian community, where can you use it?

So here’s an idea: What if we lift the moratorium on original language usage in Christian teaching? What if, instead of lumping Biblical languages in with the list of things polite people don’t bring up, we actually said, “Hey everybody, it’s time start using the languages”? Do you suppose that a student, seeing a diglot on the screen, would be more inclined to sign-up for a class? Do you think pastors would be able to retain their Biblical languages if they had congregants asking for a Greek or Hebrew Reading course? Do you think an M.Div. student would find more motivation if he was able to read along with the Sunday School teacher instead of just his Greek Prof? Do you suppose that experience would close the gap between the Church and the Academy?

I think it would fundamentally change the ethos of our community for the better. But it will require a mental shift. We’ll have to see Biblical languages as something to be cherished, not hidden.

χάρις καὶ εἰρήνη,

-Δαυιδ

Member discussion